The Analysts’ Hierarchy of Needs: Grounded Design Principles for Tailored Intelligence Analysis Tools

Antonio Girona (Pennsylvania State University), Grace B. (DoD), James Peters (NC State), Wenyuan Wang (UNC-Chapel Hill), R. Jordan Crouser (Smith College)

Introduction

In the high-stakes arena of national security, intelligence analysis is an essential foundation. Analysts sift through vast amounts of data to distill useful insights that governments rely on to make important decisions [2, 4]. Yet, the unique and intricate nature of intelligence work often outstrips the capabilities of standard analytical tools, highlighting the need for more tailored solutions that align closely with the features analysts’ value and their respective workflows.

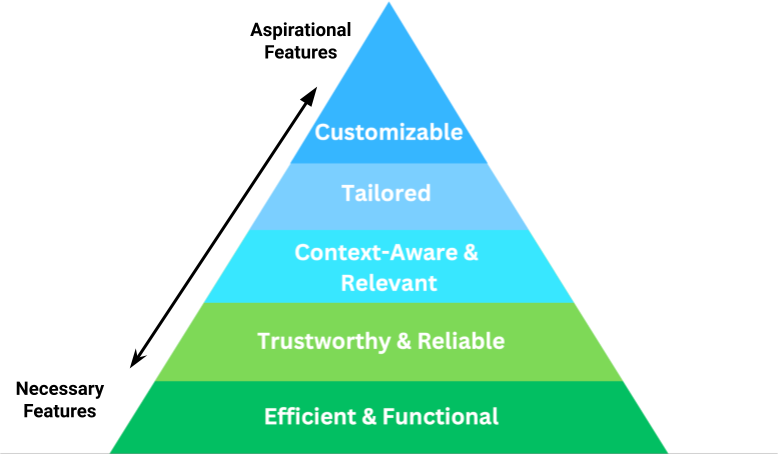

In recognition of the specific features intelligence analysts value in the tools they use, we present a new conceptual framework similar to that of Abraham Maslow’s well-known Hierarchy of Needs [5], adapted for intelligence analysts. This framework elevates the features that analysts value in the tools they use, supporting their respective workflows. As we look to the future, the potential to significantly improve the well-being and performance of intelligence analysts is within our reach, thanks to the insights from this important research.

Background

The Laboratory for Analytic Sciences hosted the 2023 Summer Conference on Applied Data Science (SCADS), which brought together experts to address key challenges in machine learning and artificial intelligence. The main goal of the conference was to develop Tailored Daily Reports (TLDRs), which are similar to the President’s daily intelligence briefings but tailored to intelligence analysts and other knowledge workers.

At the 2023 SCADS, our team’s efforts were geared towards understanding what analysts need and expect from such reports. This foundational work is a stepping stone towards developing TLDRs that are not just generic briefs, but highly customized tools that resonate with the specific requirements and workflows of intelligence analysts. By closely examining the analysts’ perspectives, we’ve started to pave the way for TLDRs that will significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of intelligence analysis.

Focused Discovery with Analysts

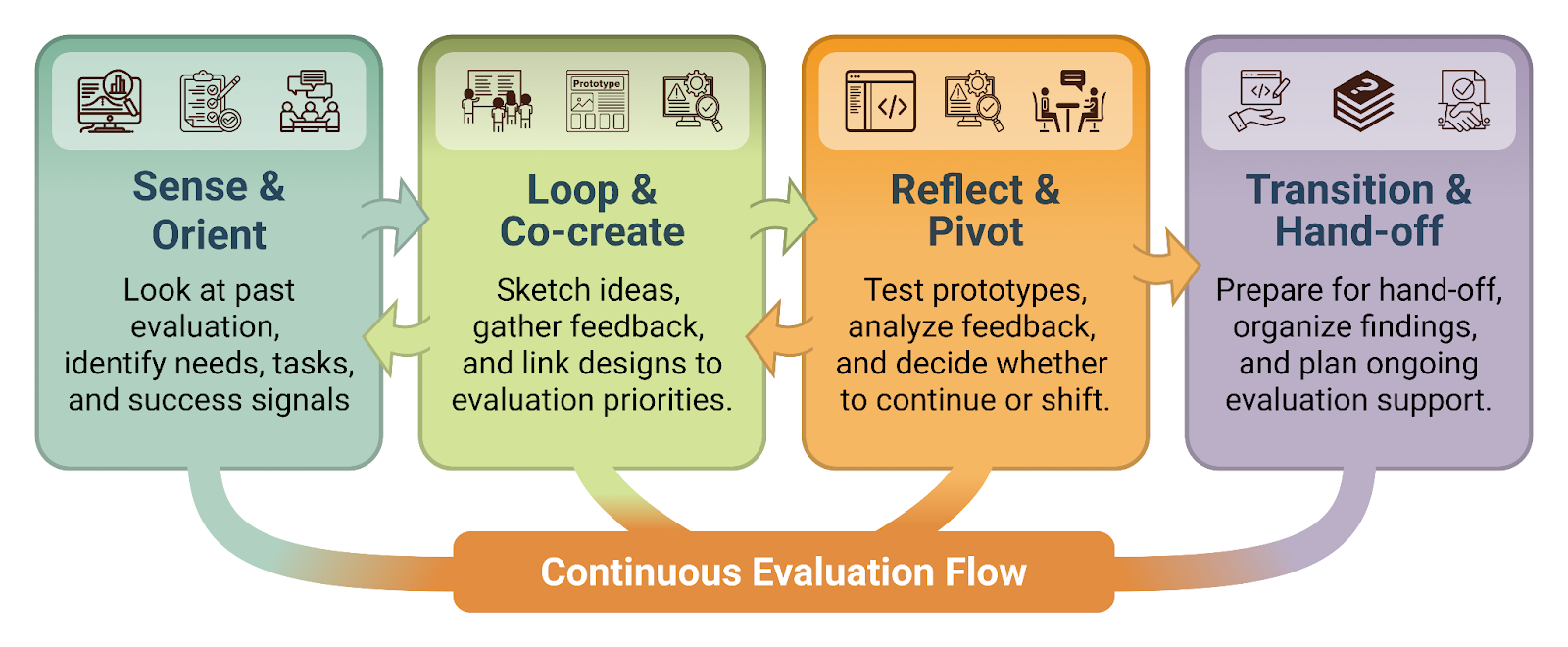

To understand the specific features analysts value, our team employed a Focused Discovery methodology. This initial phase in the UX design process centers on understanding the problem domain and defining key issues. It is the initial phase of the UK Design Council’s double-diamond model and includes ‘Discover’ and ‘Define’ stages (see Figure 2) [1]. This phase is crucial when facing unknown challenges or team misalignment, triggered by factors like market changes, policy shifts, or organizational struggles. The discovery process involves activities such as exploratory research, stakeholder interviews, and problem framing, facilitated by multidisciplinary teams. The outcomes are a comprehensive understanding of the problem, clear objectives, and potentially, initial solution concepts.

The focused discovery activity (FDA) we used for our research was an affinity diagramming exercise that involved analysts describing the desirable and undesirable features of analytic tools using sticky notes, categorizing features into related groups, and identifying essential, non-essential, and unacceptable features. We reached out to people with analyst and analyst-adjacent experience, bringing together a group with a wide range of experience from two to ten years. We assigned specific roles to each member of the project team, including facilitating discussions and taking detailed notes. We meticulously documented the process, capturing everything from initial ideas on sticky notes to the final categorization of features on a shared digital platform for comprehensive analysis.

The Analysts’ Hierarchy of Needs

Once the affinity diagramming exercises were complete, the project team analyzed the data to select codes that effectively captured the principal themes in the data as well as the processes observed during the exercises. Utilizing Charmaz’s Grounded Theory approach, a research method focused on developing inductively derived theories [2], we examined the underlying value system analysts use when evaluating potential tools to use for analysis. This rigorous approach allowed us to prioritize essential requirements based on analysts’ input, laying the groundwork for a structured framework that captures the essential features in intelligence tools. We anticipate refining this framework through ongoing analysis and data collection.

During the Focused Discovery stage, we identified several emerging themes with direct implications for the development of intelligence analysis tools. An overarching theme was the need for tools to make it easier for analysts to understand complex information quickly. Analysts often face the difficult task of making sense of a lot of data under tight deadlines. To address this, there is a pressing need for tools that not only make data easier to visualize but also make it easier to find connections and patterns in data in a way that complements the analysts’ existing workflows.

The insights from our research culminated in the creation of an Analysts’ Hierarchy of Needs (see Figure 3). At its base, the primary requirement is for tools that are not only efficient and functional but also rigorously compliant with legal standards. This foundational layer ensures that data acquisition and integration are reliable and within legal parameters. As we ascend the hierarchy, the focus shifts to establishing systems that facilitate effective collaboration and information sharing among analysts. This includes ensuring the data’s accuracy and trustworthiness, which are paramount for credible intelligence analysis. At the top of the pyramid, it’s all about giving analysts tools that ‘get’ them – systems that are smart enough to adapt to their unique needs and the ever-changing demands of their missions. This means having systems that can be finely tuned to fit each analyst’s specific role in the team, while also allowing personal tweaks to how they view and handle information. In essence, it’s about creating tools that are as dynamic and multifaceted as the analysts themselves, ensuring that the intelligence they produce is as relevant and actionable as possible.

High-Fidelity Prototype Evaluation

Evaluating the Analysts’ Hierarchy of Needs was an important next step in our research. We evaluated analysts’ feedback of two interface prototypes to support analyst workflows, developed by graduate students at the NC State College of Design, using our conceptual model as a reference. We looked at two design teams’ prototype user interfaces, each was assigned a user persona of a type of analyst in a particular scenario within a specified use case to simulate a real-world situation.

In the first case study, we evaluated analysts’ feedback on a prototype developed for a language analyst named Ron. The interface Ron was using was named “The Hive,” and his task was to sort through large amounts of data related to foreign leadership decisions. The system included features designed to use machine learning to prioritize tasks and provide contextual information. However, feedback showed that while customization and more advanced features were addressed, basic requirements such as trust and reliability were not. For example, one analyst pointed out the prototype lacked clear sources for AI-generated content and confidence metrics, which were found to be essential for the ‘trust but verify’ way of thinking, a common perspective many analysts share.

The second case study, involving the “Databoard and Sunburst Chart,” focused on the persona Nyah, a senior Search and Discovery Analyst. The interface provided various tools for data organization and situational awareness. Analysts appreciated the context-aware features and the customizable interface, but they expressed concerns about the reliability of findings generated by machine learning algorithms, stressing the importance of human-machine teaming. Moreover, the new idea of using digital watches for information flow was met with hesitancy due to security concerns, with analysts pointing out a preference for more secure alternatives like tablets.

These evaluations exposed the need for tools to have well-rounded designs that address both necessary and more aspirational features. They also serve as an example to demonstrate the continuing difficulty of leveraging emerging technologies with the critical requirements of trust and reliability in intelligence analysis tools. Future design efforts will need to prioritize a seamless blend of human judgment and technological assistance to enhance the effectiveness of intelligence operations.

Discussion & Future Work

Our research forged the foundation of a framework for better ways to manage the development of intelligence tools and support the analyst’s workflow. Our findings revealed what analysts’ value in the tools they use, enabling designers to begin developing tools with user needs in mind. To ensure our model accurately reflects the values analysts hold in the tools they use, we will engage in an ongoing, iterative collaboration with them. By taking into account analysts’ values in the tools they use, we can better understand how designers can develop tools to meet their needs. Advancing the capabilities of intelligence tools could provide analysts with a smooth and intuitive experience, enabling them to fulfill their critical role in national security with greater efficiency and accuracy.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work done, in whole or in part, in coordination with the Department of Defense (DoD). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DoD and/or any agency or entity of the United States Government.

References

[1] 2023. Design Council. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond [Online; accessed 14. Sep. 2023].

[2] Jan M. Ahrend, Marina Jirotka, and Kevin Jones. 2016. On the collaborative practices of cyber threat intelligence analysts to develop and utilize tacit Threat and Defence Knowledge. In 2016 International Conference On Cyber Situational Awareness, Data Analytics And Assessment (CyberSA). IEEE, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/CyberSA.2016.7503279

[3] Kathy Charmaz, Liska Belgrave, et al . 2012. Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft 2 (2012), 347–365.

[4] Stephen Marrin. 2009. Training and Educating U.S. Intelligence Analysts. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 22, 1 (Jan. 2009), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850600802486986

[5] Abraham H Maslow. 1943. Preface to motivation theory. Psychosomatic medicine 5, 1 (1943), 85–92.

- Categories: